The origin of Tea was with the Chinese Emperor ShenNung who was boiling water when the leaves from a nearby plant Camellia sinensis plant floated into the pot. The emperor drank the mixture and declared it gave one "vigor of body, contentment of mind, and determination of purpose." Perhaps as testament to the emperor's assessment, the potion of tea he unwittingly brewed that day, today is second only to water in worldwide consumption!"

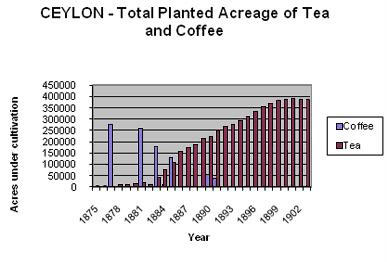

Until the 1860’s the main crop produced on the island of Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, was coffee. But in 1869, the coffee-rust fungus, Hemileiavastatrix, killed the majority of the coffee plants and estate owners had to diversify into other crops in order to avoid total ruin. The owners of Loolecondera Estate had been interested in tea since the late 1850’s and in 1866, James Taylor, a recently arrived Scot, was selected to be in charge of the first sowing of tea seeds in 1867, on 19 acres of land. Taylor had acquired some basic knowledge of tea cultivation in North India and made some initial experiments in manufacture, using his bungalow verandah as the factory and rolling the leaf by hand on tables. Firing of the oxidized leaf was carried out on clay stoves over charcoal fires with the leaf on wire trays. His first teas were sold locally and were declared delicious. By 1872, Taylor had a fully equipped factory, and, in 1873, his first quality teas were sold for a very good price at the London auction. Through his dedication and determination, Taylor was largely responsible for the early success of the tea crop in Ceylon. Between 1873 and 1880, production rose from just 23 pounds to 81.3 tons, and by 1890, to 22,899.8 tons. The first vessel recorded as carrying Ceylon tea to England was the steam-ship ‘Duke Argyll’ in 1877.

Rapid expansion of the Ceylon's tea industry in the 1870s and 80s brought a good deal of interest from the large British companies, which took over many of the small estates. Four estates were purchased by a grocer whose name is almost a synonym for tea: Thomas J. Lipton. Son of poor Irish immigrants, Lipton grew up amidst the slums of Glasgow. He left school at the age of 10 to help support his family and in 1865 sailed to America to work as a manual laborer and later managed a successful New York grocery store. It was here that he learned all the tricks and techniques of advertising and salesmanship that he later used to great effect when selling groceries and tea back in England and Scotland. He returned to Glasgow in 1871 and worked for a couple of years in the grocery shop run by his parents. By the age of 21, he had opened his own store, where he practiced the retailing skills he had learned in America. His imaginative marketing and clever publicity stunts brought his new venture rapid success. In 1890, already a millionaire, Lipton was in need of a holiday and booked a passage to Australia. On the way, he broke his journey in Ceylon. He had an interest in tea as a product to sell in his shops. Lipton did not trust middlemen, and wanted to explore the possibilities of growing tea and bringing it direct to Britain. He couldn't have picked a better time. Since the problems of the coffee blight, plantations in the island were going for a song. He bought four and could now fully control his company's tea's quality and price. Tea was quite expensive in Britain at that time, and was selling at a higher price than most working-class families could easily afford. Lipton's plan was to reduce its cost by cutting out the numerous middlemen, and render it affordable for the average British shopper. His other novel idea was to begin packaging it. Instead of selling it loose from the chest, as was the custom at that time, Lipton packed his tea in brightly-colored, eye-catching packets bearing the slogan "Straight from the tea gardens to the tea pot." Lipton's foray into tea was a huge success, and vastly increased his wealth. His 300 shops throughout England soon could not keep up with the growing demand for his inexpensive product, and so Lipton teas became available in other stores around Britain. The name of Lipton had migrated from a chain of grocery stores and became a trademark soon to be famous the world-over. James Taylor's legacy, on the other hand, is best summed up in the words of John Field, High Commissioner for Great Britain in Sri Lanka. In 1992 he wrote, "It can be said of very few individuals that their labors have helped to shape the landscape of a country. But the beauty of the hill country as it now appears owes much to the inspiration of James Taylor, the man who introduced tea cultivation to Sri Lanka."

Henry Randolph Trafford was born in on 8 December 1853, the second son of Charles Guy Trafford and Caroline Anne, née Hopton. He was educated at Bradfield College (1868-1872), and Christ Church, Oxford University (1873-1875), though he did not graduate. According to his daughter, in her unpublished memoirs, Henry’s decision to move to Ceylon was motivated by family difficulties. On 22 February 1877, Henry left Southampton as a first class passenger on the SS Peshawur, bound for Ceylon. The SS Peshawur docked at the harbour at Galle, Ceylon on the morning of 24 March 1877. Henry kept a detailed journal of the month long journey and his first few weeks in Ceylon. This is how he had described his arrival in Galle,

‘Never did anything appear so truly beautiful to me as this, my first sight of Ceylon: the sweet little bay dotted here and there with various craft of various build and rig; a regular forest of palms coming right down to the beach, gracing the shore with their rich verdancy, and behind all the most glorious sunrise I ever saw, giving a bright golden tinge to the brilliant mass of green. Truly indeed, I thought does this deserve the name of the earthly paradise.’ ‘This first sight of Ceylon will be forever imprinted on my memory; it will always seem to me like a glimpse into Fairyland’.

Henry had a letter of introduction to the Peradeniya coffee estate, in the Hantane district, a few miles west of Kandy, owned at the time by Baring Brothers and Co. It was here that he would learn the business of coffee growing, before buying his own estate at Poyston. Poyston is located in Ceylon’s hill country, in the district of Dickoya, about 4,000 feet above sea level. It is just a couple of miles from the large Norwood Estate, in an area that holds a cluster of world renowned tea plantations (sometimes known as the Golden Valley of Tea). Poyston Tea Estate remains in existence as a tea estate to this day. The years until 1887 must have been hard graft for Henry. But as the changeover to tea was made, and as Henry became a long-standing member of the community (voting at the Planters’ Association of Ceylon in Kandy from 1885-1891), he was clearly able to relax more. In 1887, he was a member of the committee of the prestigious Kandy Club (whose President was the Governor of Ceylon), as well as being a member of the committee of the Dickoya Planters’ Association (a position he held until 1890). The extension of the railway line in 1884 to Hatton, less than 10 km from Poyston, would have made the journey time to Kandy considerably shorter and easier (less than three and a half hours by train from Hatton). The only surviving photograph from Henry’s stay in Ceylon is a group photograph from the Darrawella Club. He may also just have missed the visit on 14 February 1891 to the Darrawella Club of the Tsaravitch, later Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia. It seems unlikely that Henry made any money from his tea estate in Ceylon. Indeed, by all accounts, he lost money. But against this he surely deserves the recognition – if more by chance than good judgment – of being one of the pioneers of Ceylon tea.

Tea plant belongs to the genus Camellia and of the species: sinensis [from China] and assamica [from Assam] but is now commonly referred to simply as: Camellia sinensis. Today, a vast number of hybrids exist, developed to take advantage of the strengths and weaknesses of each variety, and to adapt plants to the specific geographical and climatic circumstances of each area. The plants did not figure among the local flora on the island of Ceylon, a British crown colony, until the early 19th century when several entrepreneurs used their estates as test plots. In 1839, Dr. Wallich, head of the botanical garden in Calcutta, sent several Assam tea plant seeds to the Peradeniya Estates near Kandy. This initial consignment was followed by two hundred and fifty plants, some of which went to NuwaraEliya, a health resort to the south of Kandy at an altitude of 6,500 feet. The NuwaraEliya experiment produced excellent results. Seeds of Chinese tea plants, brought to Sri Lanka by travellers such as Maurice de Worms, were also planted in the Peradeniya nurseries, although these yielded disappointing results and Chinese plants were gradually abandoned in favour of the Assam variety that is now grown on every estate in Sri Lanka. Tea cultivation nevertheless remained a minor activity for twenty years. Coffee remained the island's main export crop. However in the 1870s the dreaded blight systematically destroyed coffee plants. The entire coffee industry was destroyed. Tea then appeared as a godsend and the entire local economy shifted to the new crop within a few years. This rapid substitution owed a great deal to the fruitful initiative of a man named James Taylor.

In 1851, near Mincing Lane, which was later renowned as the tea center of the world, Taylor had signed on for three years as an assistant supervisor on a coffee plantation in Ceylon. The sixteen year old Scot, son of a modest wheelwright, would never see his native land again. Five years after he took up his post, his employers, Harrison and Leake, impressed by the quality of his work, put Taylor in charge of the Loolecondera Estate and instructed him to experiment with tea plants. The Peradeniya nursery supplied him with his first seeds around 1860. Taylor then set up the first tea factory on the island. It was in fact a rather rudimentary set up. The factory soon became famous throughout the island. In 1872, Taylor invented a machine for rolling leaves, and one year later sent twenty-three pounds of tea to Mincing Lane. Taylor trained a number of assistants, and from that point on; Ceylon tea arrived regularly in London and Melbourne. Its success led to the opening of an auction market in Colombo in 1883, and to the founding of a Colombo tea dealer's association in 1894. Taylor continued to test new methods and techniques at the Loolecondera Estate (which he would never own) until the end of his life. He never left the estate, except for a single short vacation in 1874 spent at Darjeeling, needless to say, in order to study the new tea plantations. His talent and determination were officially recognised when Sir William Gregory, Governor of Ceylon, paid Taylor a visit in 1890 to congratulate him on the quality of his tea. But the rise of the industry nurtured by James Taylor was also the cause of his downfall. Rapid growth was accompanied by a concentration of capital in the hands of large Corporations based in Britain, and a wave of property consolidation forced out smaller planters. Interestingly, Lovers' Leap is the first and only tea garden owned by James Taylor, the Pioneer of Tea Industry in Sri Lanka. In 1892, he died suddenly of dysentery at the age of fifty-seven, on his beloved soil at Loolecondera. His grave in Mahaiyawa Cemetery is inscribed as follows,

"In pious memory of James Taylor, Loolecondera Estate, Ceylon, the pioneer of tea and cinchona enterprise, who died on May 2, 1892, aged 57 years".

The 1884 and 1886 International Expositions held in London introduced the English and foreigners to teas produced in the British Empire. But it was at the 1893 World Fair in Chicago that Ceylon tea made a tremendous hit; no less than one million packets were sold. Finally at the Paris exposition of 1900, visitors to the Sri Lanka Pavilion discovered replica tea factories and the five o-clock tea that became so fashionable. The promotional policy was so effective that by the end of the 19th century, the world tea was no longer associated with China, but with Ceylon. The island's prosperity sparked covetousness on the part of British companies and London brokers, who wanted to acquire their own plantations and cut out the middlemen. This marked a turning point in the saga of tea; pioneers gave way to merchants whose name or label would soon become more important than the country in which the tea was grown.